Economic Freedom Is Key to African Development

Secure Property Rights, Institutional Reform, and Affordable Energy Can Unlock Prosperity for Africa

Many African nations have made great economic strides in recent years. As well as improving Africa’s per capita GDP by over 50 percent since 2000, some have made leaps forward in technological development. Examples include the cell phone revolution and the widespread adoption of digital cash in Kenya. In countries with poor landline telecommunication systems and limited access to finance, poor people are leapfrogging past old problems through the adoption of new technologies. Yet that is only a start. While these advances have made life better for millions of Africans, most Western approaches to development, whether at government agencies or the leading non-government organizations, neglect the importance of three key building blocks of prosperity: secure property rights, limited government, and affordable energy.

Examples of this approach can be seen in the 2017 edition of the Brookings Institution’s annual Foresight Africa report, which seeks to highlight top priorities for the continent. This year’s report has much to applaud, such as its focus on attracting investment, supporting technological uptake, and improving accountability in governance. However, it overlooks viable solutions to two key priorities in African development—how to legitimize beneficial but currently technically illegal activities and how to power the region’s economies. African policy makers should augment Brookings’ recommendations with policies that promote economic freedom, limited government, and affordable, plentiful energy.

Freedom and Formalization. One of the development community’s most often cited priorities is the need for African economies to “formalize” their economies. This means shifting business activities from operating outside a country’s legal framework toward a status recognized and protected by law. There are many benefits to formalization. Registered companies have greater productivity and investment, create more jobs and growth, and enjoy legal protection against fraud for both themselves and their customers. They also have access to credit and capital, which provides opportunities for growth.

Studies conducted across Sub-Saharan Africa estimate the informal economy accounts for some 50 to 80 percent of the region’s GDP, 60 to 80 percent of employment, and as much as 90 percent of new jobs. This shadow economy is a natural response to the stifling restrictions governments place upon businesses. As Nigerian political commentator Olumayowa Okdediran notes: “Without the rule of law, it’s quite difficult to make a living, but people do it. They rely, not on the state, which is often a failure, but on traditional African customary law.” So while informal economies may be a necessity, driving so much economic activity underground creates insecurity that stunts development, distorts the rule of law, hinders market formation, and impedes growth.

While thousands of pages have been written lamenting the prevalence of economic informality in the developing world, few have attempted to tackle the root cause of the problem. Experts often blame lack of infrastructure, education and skills training, and limited access to technology. Overwhelmingly, however, informality is due to government policies that restrict economic liberty. By imposing burdensome barriers to marketplace entry, many governments prevent formalization. As Huzaifa Shabbir Hussain of the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) argues: “When taxes are too high, business regulations too onerous, and private property rights inaccessible for many, businesses that would otherwise enter the formal economy cannot.” What Africa needs is a dose of economic freedom.

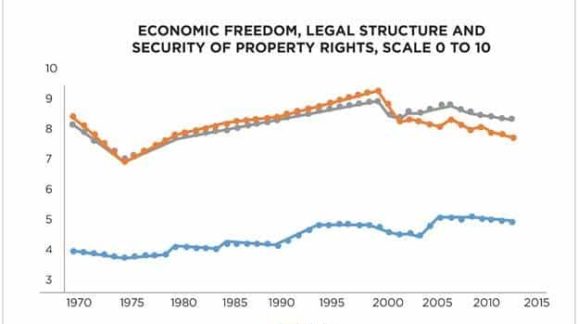

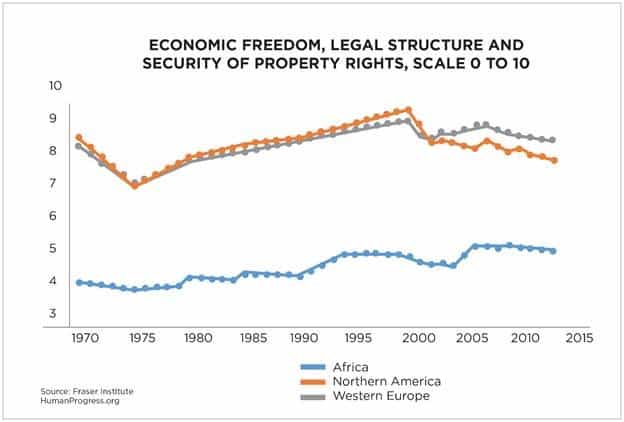

Establish Secure Property Rights. Secure, strong property rights are a cornerstone of economic freedom. They enable individuals to trade, gain access to finance, and claim damages through the justice system. They are also a historically proven key to development. Nations with the strongest private property protections have per capita incomes five times higher than those with only moderate protections. African governments should make it as easy and efficient as possible to establish recognized property rights. Without formal land titles, impoverished Africans cannot leverage their assets to borrow money and start businesses or be assured just compensation if their property is damaged or stolen. The renowned Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto estimates that around $10 trillion worldwide is locked away as “dead capital,” much of it in Africa. Instead of liberating this wealth, governments have erected costly barriers to registration. Bureaucracy, regulation, and corruption plague many government land registration systems.

Rather than rely on outdated regulatory structures, African nations could follow in the footsteps of countries like the Republic of Georgia to establish land registry systems using blockchain technology. The blockchain, a widely accessible online public ledger that can log land titles digitally, provides a more secure and efficient alternative to slow, bureaucratic government systems. According to the World Bank, it can take nearly 60 days and cost up to 8 percent of the property’s value to register in Africa. In Nigeria, one of the region’s largest economies, the registration process takes an average of 77 days and 10 percent of the value of the property. Outsourcing the process will reduce costs significantly, to as little as $0.5 to $0.10, while saving many hours of paperwork.

Perhaps most critically, the distributed nature of the ledger can help prevent fraud by enabling the establishment of a largely tamper-proof means of titling land, out of the hands of corruption-prone officials. Property fraud is rife in Africa, so securing property rights would be a critical first step in fostering a more robust rule of law. While blockchain titling programs are currently being piloted in southern Ghana, policy makers in other African nations should look for ways to take advantage of such innovative technologies in order to give their people greater security in their property.

Reduce the Burden of Government. For decades, many African governments have actively discouraged market participants by fostering a hostile business environment. While profit, trade, and entrepreneurship can be found to varying degrees in all African economies, anti-business policies stifle the ability of many to participate in the formal economy. High taxes and burdensome regulation discourage potential entrepreneurs from starting businesses and expanding them. As the CIPE Director Andrew Wilson argues: “Research has consistently shown that entry barriers such as lengthy registration requirements, licensing and inspection requirements, and complicated taxation policy are the key reasons for people remaining in the informal sector.”

Although there has been substantial progress, African regulatory requirements continue to stifle growth. The most recent edition of the Economic Freedom of the World report, co-published by the Cato Institute and the Fraser Institute, found that Africa ranked at the bottom globally in terms of economic freedom. And the World Bank’s recent Ease of Doing Business Report deemed Africa the most difficult region in the world for starting a business. On average, an African entrepreneur will spend 54 percent of his or her annual income and take around 27 days to register a new business. In some African nations, this can consume up to 422 percent of per capita income and take around 134 days. African firms are the most highly taxed in the world. Taxes total 47 percent on average as a percentage of profits.

African entrepreneurs invest in informal channels to reduce these regulatory costs. It is a rational reaction to burdensome government requirements. To attract businesses into the formal economy, governments must stop creating perverse incentives that drive businesses away. To spur growth and employment, regulatory mandates and taxes must be dramatically scaled back.

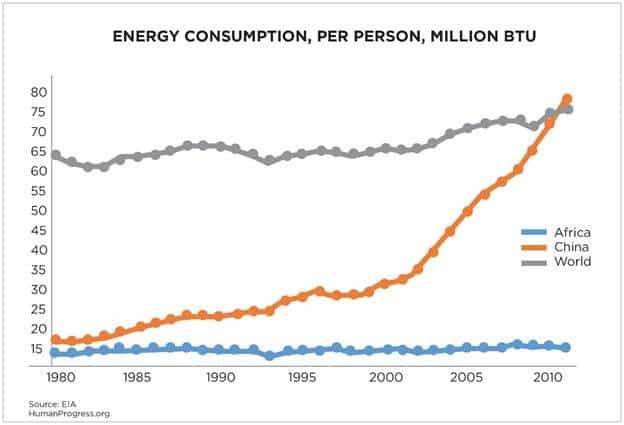

Power Africa through Fossil Fuels. Economic development requires affordable, plentiful energy. With over 620 million Africans lacking any access to electricity, the shortage remains one of the most formidable barriers to growth. Inadequate access to energy not only traps millions in poverty, it also inhibits progress toward other important goals, such as curing avoidable diseases, providing universal education, and improving sustainable land use. The broader impact of energy poverty is made starkly obvious by Africa’s reliance on biomass fuels. Without accessible energy, impoverished Africans are forced to burn wood for cooking and heating, leading to rampant deforestation and indoor air pollution. This kills over 600,000 people across the continent each year. Energy poverty is a crushing reality, and if Africa is to develop, it must overcome it.

Given this urgency, it is disappointing how little importance many in the international development community place on promoting access to efficient, affordable energy. Many contend that we can power African development through low-emission renewable energy technologies designed to mitigate climate change. The problem with this proposition is twofold. First, current technology renders renewable energy both inefficient and expensive, especially for large scale industrialization. Second, the perceived costs of climate change, assuming they are correct, do not outweigh the benefits of a developed Africa.

Alternatives to fossil fuel energy are fundamentally constrained by their high cost and relative technological immaturity. In developed nations, they remain dependent upon government support, and they cannot provide anywhere near the amount of energy needed to power modern life. If innovation could reduce the price and improve the capacity of renewables, then Africa should undoubtedly pursue them. But this is currently not the case.

Africa does not need small-scale off-grid solutions. It needs extensive, reliable energy sources to drive a modern economy of industry, agriculture, and services. Intermittent renewables struggle to provide this. As the World Bank has noted: “[T]here’s never been a country that has developed with intermittent power.” Forcing an energy impoverished continent onto an energy diet would be highly destructive. At the recent World Economic Forum on Powering Africa, one panelist stressed that for Africans, it is “not just getting them a lamp and a cell phone charger. It’s getting them the productive demand so that … the manufacturing and industrialization takes place too.” Africa should invest in the most effective source of energy to drive a modern economy. For now, that is fossil fuels.

Even when accepting the fact that fossil fuels are currently the most feasible option, green energy advocates argue that hefty increases in emissions will raise future costs, tipping the scale in the opposite direction. Yet, fossil fuel-driven development significantly outweighs climate adaption costs. For example, Brookings argues that climate adaptation currently costs African economies around 1.4 percent of GDP, growing to around 3 percent per year by 2030. At the same time, as Brookings has found elsewhere, inadequate power diminishes the region’s current growth by 2 to 4 percent per year. Under this simple cost-benefit analysis, it pays to pursue affordable energy.

The benefits do not end there. The International Energy Agency estimates that sub-Saharan Africa could become almost $7 trillion richer by 2040 through aggressively pursuing fossil fuels. The IEA study concludes that the region’s economy will likely grow 30 percent larger by pursuing traditional energy rather than a fossil fuel-renewable energy mix, increasing GDP by over double its current levels.

Furthermore, concerns associated with increased emissions are largely overstated. Under the IEA’s highest growth scenario, sub-Saharan Africa’s share of global emissions is projected to increase to a mere 4 percent by 2040, up from 1.8 percent in 2012. An alternative scenario explored by the International Association for Energy Economics reports that fueling African development entirely on fossil fuels will increase total global emissions by as little as 2 percent of current levels. This simply does not provide a case for severely limiting affordable energy.

Energy use should be predominately assessed on the basis of sustainability, cost, and availability. The extent to which millions of Africans are trapped in extreme poverty is a higher priority than mild and manageable emissions. Yet, climate activists continue to advocate for policies that would regulate away one of the developing world’s most important resources to break out of poverty. Treaties that aim to restrict carbon energy use, like the Paris Climate Agreement, could be damaging to wealthy economies, but devastating to poor ones.

For instance, in order to achieve the Paris Climate Agreement’s goal of limiting warming to 2°C, developing countries must dramatically reduce their current emissions by 2050. As the Competitive Enterprise Institute’s Marlo Lewis notes, this limit cannot be achieved without imposing painful sacrifices on developing countries. Even if industrialized countries were to reduce their current emissions by an incredible 80 percent, developing countries would have to cut theirs by 48 percent. How are developing nations supposed to simultaneously eradicate energy poverty while reducing their consumption of the world’s most abundant, affordable, and reliable energy sources by almost half?

Renewable energy advocates tend to focus on the costs associated with fossil fuels, while neglecting the fact that the economic growth they bring increases our ability to innovate, adapt to changes, and even improve the environment. As Bjorn Lomborg, author of The Skeptical Environmentalist, notes: “In wealthy countries, campaigners emphasize that a ton of CO2 could cost some $50. … But for Africa, the economic, social, and environmental benefits of more energy and higher CO2 run to more than $2,000 per ton.” Affordable, reliable access to electricity could provide for the one-third of all health centers and primary schools that currently go without power, for the half of African businesses stating that lack of access to power affects their operations and growth, and for the millions afflicted by indoor air pollution, contaminated water, and disease.

Reliable, affordable energy powers modern agriculture, industrial production, and economic growth. African Development Bank President Akinwumi Adesina recently said: “In Africa, we just need to learn from what’s working, and scale it up.” Ever since the industrial revolution, what has worked to secure reliable energy has been fossil fuels. African policy makers should invest in resources to spur their development most effectively. As Obama White House science advisor John Holdren wrote years ago, “Affordable energy in ample quantities is the lifeblood of the industrial societies and a prerequisite for the economic development of the others.”

Conclusion. It is encouraging that development leaders are increasingly committed to pro-market reforms. For example, the latest edition of the Brookings Institution’s Foresight Africa report outlines strategies to attract investment, boost transformational technology, and uphold good governance. Other experts are beginning to reject foreign aid programs, state-led industrialization, and protectionism. These are all positive signs. However, if African nations are to achieve the dramatic economic transformation they need, there are other important lessons to follow.

Establishing secure property rights and an attractive tax and regulatory environment are critical to developing credit markets, attracting investment, and fostering formal economies. Further, allowing Africa to pursue independently the many affordable, effective sources of energy will power the industrialization it seeks. African policy makers should strive to implement these pro-growth policies so as to achieve the prosperity their nations deserve.