Stop Making Sense: Reviving the Robinson-Patman Act and the Economics of Intermediate Price Discrimination

I. Introduction

Early in the 20th century, a new model for retail sales arose: chain stores. One chain, the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company (A&P), became America’s largest retailer during 40 mid-century years. Emphasizing scale, vertical integration, and superior use of data, chain stores had lower costs, greater variety, and often other measures of improved quality. The previously dominant model featured wholesalers, middlemen who connected manufacturers, many growing in size, to the myriad, mostly small retailers. Incumbent retailers and wholesalers reacted fiercely to the new competition, attempting to use government to limit their growing, more efficient rivals.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s first attempt to end the Great Depression, the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, preached business-government cooperation and sought to raise prices to provide relief to struggling businesses. Chain store opponents seized the opportunity. Under the new law, codes of conduct emerged, some of which attempted to prevent chain stores from bypassing traditional wholesalers, while others aimed at crippling the new model. In practice, the codes proved hard to enforce, and the Supreme Court ended the experiment less than two years after the underlying statute was enacted, declaring it unconstitutional.

Eleven days after the Court’s decision, Rep. Wright Patman (D-TX) introduced new legislation, the Wholesale Grocer’s Protection Act. The bill, unsurprisingly, was written by the wholesalers’ trade association. Sen. Joseph Robinson (D-AR) quickly agreed to be the Senate sponsor. Following the codes, the statute attempted to cripple chain stores and preserve the dominant wholesaler model. Many objected, most prominently the Roosevelt administration, and the sponsors were forced to compromise, adding defenses, other provisions, and a great deal of ambiguity.

Despite Congress’s refusal to pass the overtly protectionist original bill, the FTC made a protectionist interpretation of Robinson-Patman, its major competition enforcement weapon through the 1960s. By the 1970s, however, at least two interrelated events led the FTC to reverse course. First, the battle over chain stores had ended, with the chains emerging as the clear victors. While small business lobbies would routinely praise Robinson-Patman, the dominant wholesalers that led the original fight had long since been eclipsed. Second, in virtually all quarters of the antitrust community outside of the FTC, firsthand experience with Robinson-Patman led to condemnation. Those within antitrust recognized that the Act operated to protect competitors, while the rest of antitrust law focused (in principle if not always in practice) on competition and competition’s main beneficiaries, consumers.

This recognition left Robinson-Patman an embarrassing orphan. Although eventual FTC deemphasis provided far fewer opportunities for judicial review, courts increasingly interpreted Robinson-Patman in a manner consistent with the rest of antitrust law. Deemphasis continued at the FTC until the Biden administration filed the first two cases in decades as that administration ended. The Trump FTC closed one case, but continues the other.

Current calls to revive federal enforcement of the long dormant Robinson-Patman Act emphasize how large buyers, but not their small competitors, obtain substantial volume discounts from manufacturers. Powerful buyers, exercising monopsony power, have long been a legitimate antitrust concern. Besides harming sellers, classic monopsony decreases output in the product market, raises retail prices to consumers, and lowers both consumer and total welfare.

Firms with buyer power, however, can also benefit consumers as A&P did long ago. Modern large chain retailers such as Walmart receive volume discounts from suppliers and have updated the original chain store formula. There is credible, causal empirical research that the entry of such firms increases competition, expands market output, and generates large consumer benefits through lower prices and improving quality. This evidence is inconsistent with classic monopsony and the associated negative upstream and downstream welfare effects.

Despite evidence of increased competition and consumer benefits, Robinson-Patman revivalists target volume discounts and the firms that obtain them. We examine the economic literature regarding intermediate price discrimination, and its bearing on the revivalist claims. Section II examines two theories involving differential versus uniform intermediate good pricing. The first is the economically incoherent notion of “subsidy effects”—the claim that large discounts to large buyers are necessarily subsidized by higher prices that small buyers pay. The second is the generation of “waterbed effects,” where input prices fall for one type of retailer and rise for another compared to a regime where input prices must be uniform. Neither theory provides meaningful support for reviving Robinson-Patman. Section III briefly reviews the modern economic literature on intermediate good price discrimination, describing key assumptions necessary to produce welfare losses from intermediate good price discrimination. The negative welfare effects of allowing intermediate good price discrimination are often reversed when the assumptions that sellers use take-it or leave-it offers for linear (constant per-unit input) prices are replaced with bargaining and non-linear pricing via two-part tariffs—assumptions that better match actual market conditions in many, if not most, cases.

Section IV analyzes a common form of non-linear intermediate good pricing, all-units volume discounts. The analysis shows how these commonly used discounts produce effects similar to those of the two-part tariffs examined in Section III. Section V examines two recent empirical analyses used to simulate the effects of limiting intermediate good price discrimination. Neither provides evidence that would support a Robinson-Patman revival. Section VI concludes, noting that while some the theories used to justify renewed Robinson-Patman emphasis contribute to economic theory, others are nonsensical, and none are useful for guiding public policy. Moreover, for any pricing practices that do raise serious issues, the Sherman and Clayton Acts law are the appropriate vehicles to analyze the relevant costs and benefits, not a statute that makes such determination difficult, at best.

II. Uniform vs. Differential Pricing and Waterbed Effects

Robinson-Patman revivalists claim that discounts to large buyers cause manufacturers to raise prices to smaller retailers to recoup the lost revenues and profits from the discounts. These “subsidy effects” accelerate the exit of smaller retailers, reducing competition to the detriment of consumers. Robinson-Patman enforcement would allegedly prevent or diminish such harms.

This argument is economically incoherent. If a seller can raise the price to smaller retailers, it will do so, regardless of its bargaining with larger customers. Suppose two retailers, RL and RS (the smaller one), operate in separate geographic markets and do not compete with each other (known as the independent demand case). If the upstream seller has set the profit-maximizing price to RS before it contracts with RL, it would actually earn less profit by increasing the price to RS because the raised price would be higher than optimal. If RL and RS instead compete in the same antitrust market (known as the interdependent demand case), the profit-maximizing price to RS would in fact decrease if the large retailer (RL) obtains a more favorable input price. That is because the lower price to RL will be passed through partially to its consumers. As a result, the demand facing RS will shift inward, as some consumers shift from buying from RS to RL. This shift in demand results in downward pricing pressure, and the upstream firm’s profit maximizing selling price to RS would fall. Thus, in contrast to the “subsidy” scenario, economic analysis predicts the opposite effects of those revivalists claim.

Some revivalists avoid this economically incoherent “subsidy effects” argument and instead rely on economic articles that show intermediate good price discrimination generates “equilibrium waterbed effects” that can reduce welfare compared to a regime where input prices must be uniform. Under differential pricing, prices will reflect differences in downstream buyers’ costs and demand, the nature of downstream competition, pass-through rates, bargaining power, and non-linear components to input prices. Compared to uniform equilibrium intermediate prices, some downstream buyers necessarily will pay higher prices, while others will pay less. In the long run, differential input prices could weaken some retailers, potentially leading to their exit. Because these equilibrium waterbed effects are generated using internally consistent economic models, they differ from incoherent subsidy effects.

These models provide neither strong support nor useful guidance for reviving Robinson-Patman. While economists have modeled scenarios in which differential input pricing results in equilibrium waterbed effects that decrease consumer welfare, whether input prices increase or decrease, and whether welfare decreases or increases, depends on both the specific assumptions of the model and its parameters. An equilibrium waterbed effect is one of the many economic theories in modern industrial organization economics that postulate difficult to observe and measure conditions under which common business practices might be either anti- or pro-competitive. Most economists, including those writing about waterbed effects, recognize the potential pro-consumer benefits of differential pricing, including beneficial long-term effects. The authors of one of the theoretical papers themselves recently stressed the limitations of the often-contradictory theoretical economic literature, especially given the limited empirical evidence available.

The analyses in these models also contain other assumptions that limit their ability to guide public policy. For example, they use specific and often unrealistic models of downstream competition. Moreover, the models generally assume a single upstream seller, and do not address the effects of intermediate good price discrimination with strategic interaction between multiple upstream sellers. Thus, such models would analyze Coke’s pricing decisions in a world where Pepsi is assumed not to exist. Additionally, the results from existing models of intermediate good price discrimination appear to be sensitive to this assumption. In fact, models of price discrimination in final goods markets (where sellers can use discriminatory prices when they sell directly to consumers) that include strategic interaction between competing sellers produce different results than price discrimination models with a monopoly seller. Rather than raising prices to some consumer groups and lowering them for others, these models find that price discrimination can intensify competition in oligopolistic markets, leading to lower prices for all consumers.

Crucially, the Robinson-Patman Act itself does not mandate the price uniformity on which the models rely. By its terms, the Act permits nonuniformity if justified by certain conditions, such as a party’s costs and relevant competitive conditions. The proper interpretation of the statute was never obvious, and the FTC’s decades-long enforcement that favored competitors over consumers, largely abandoned after 1970, left a significant body of internal FTC law and some supportive federal court decisions. Led by the Supreme Court, modern courts have insisted that Robinson-Patman be interpreted as consistent with the rest of antitrust law, but, with the FTC’s retreat, opportunities for reconciliation consistent with that mandate have been relatively few.

Thus, given the ambiguity of the practices at issue, assuming anticompetitive waterbed effects have any empirical significance, the appropriate policy would weigh both benefits and costs. Existing Sherman and Clayton Act precedent already allows antitrust law to apply that policy without attempting to revisit a statute ill-suited to the task.

III. The Economic Analysis of Differential Input Pricing

Michael Katz’s 1987 article helped produce a new economic literature on intermediate good price discrimination. Katz was one of the first to demonstrate how intermediate price discrimination, by affecting downstream competition, could produce different effects than price discrimination in final goods markets. Katz’s model analyzed intermediate price discrimination that raises average input and consumer prices and lowers output and welfare compared to requiring uniform input prices.

In this model, an upstream monopolist sets linear prices to two downstream retailers in multiple markets. In each downstream market, one retailer is a chain store that sells in many markets, while the other is an independent retailer. The two stores in each downstream market compete as Cournot competitors. A key assumption of the model is that only chain stores, not independent stores, can integrate backwards. The chain’s threat to integrate constrains the upstream firm’s price to the chain. When this constraint is binding, the linear input price is set so that the chain chooses not to integrate whether prices are uniform or differential. This allows intermediate good price discrimination to raise input and final good prices, reducing output and welfare.

While Katz demonstrates that such negative price and welfare effects of intermediate good price discrimination are possible theoretically, these effects can be reversed if key assumptions of the model are relaxed. Besides the assumption that only the chain store, but not independents, can integrate backwards, key assumptions include that the upstream supplier makes take-it or leave-it offers to the downstream retailers, and that input prices are linear.

In 2014, Daniel O’Brien modified Katz’s model by replacing the upstream sellers’ take-it or leave-it offer with a bargaining framework containing multiple sources of bargaining power. O’Brien demonstrates that Katz’s positive welfare effects from forbidding intermediate good price discrimination flow from the binding integration constraint. If this constraint is not binding because other sources of bargaining power provide tighter constraints, forbidding price discrimination reduces rather than increases the average wholesale price across a wide range of parameters that determine the bargaining outcome.

While noting that no direct test of the causal effects of the passage of the Robinson-Patman Act exists, O’Brien notes that indirect empirical evidence is more consistent with the theoretical predictions from the expanded bargaining model than the predictions from Katz’s take-it or leave-it model. If retailers with a credible binding threat to integrate backwards were common, input prices should have fallen after the Act’s passage, making suppliers worse off and benefiting retailers and consumers. In reality, the Act’s effect suggests that the opposite occurred. For example, Adelman’s study of the wholesale purchasing and pricing practices of A&P found that suppliers that sold to A&P were better off after the passage of Robinson-Patman. Moreover, Ross studied the stock price effect of passage and enforcement of the Robinson-Patman on firms, including suppliers and downstream retail firms. He found that the Act led to negative, abnormal returns for grocery chains.

Non-linear pricing also reverses the negative welfare effects of intermediate price discrimination that Katz modeled. O’Brien and Shaffer examine the effects of intermediate good differential pricing when upstream sellers use non-linear pricing (two-part tariffs), and the upstream and downstream firms bargain over the terms. In their model, the upstream manufacturer charges the downstream retailers a fixed fee in addition to a per-unit input price. In the absence of wholesale price regulation, upstream sellers use efficient two-part tariffs, with all retailers charged a per-unit input price equal to the manufacturer’s marginal cost. When inputs are priced at marginal cost, the downstream retailer’s optimal retail price equals the joint profit maximizing price. The seller extracts surplus through bargaining over the size of the fixed fee. Unlike the previous models using linear pricing, these models produce discriminatory discounts that favor large retailers and disfavor smaller ones.

In contrast, with mandatory uniform wholesale unit prices, the manufacturer will instead extract some of the surplus through a per-unit input price that exceeds the manufacturer’s marginal cost. The authors examine three alternative settings: where the manufacturer can only charge a uniform input price; where both the unit price and the lump sum fee must be uniform; or where the unit price must be uniform, but the lump sum fee can vary. The main result, reduced consumer welfare when input prices are regulated, applies to all three variations examined. In the first case, regulation produces high linear input prices due to double marginalization. Whether uniform or discriminatory fixed fees are allowed, forbidding discriminatory unit pricing (through Robinson-Patman enforcement or other means) diminishes retailer incentives to bargain for lower wholesale prices because rivals must also receive any price concession the retailer bargains for. This leads the supplier to extract some of the surplus through an input price that exceeds marginal cost rather than through the lump sum fee. The result is higher equilibrium wholesale and retail prices, and lower total and consumer welfare under all three regulatory regimes that mandate uniform unit pricing.

IV. The Economics of Volume Discounts and the Elimination of Double Marginalization

The non-linear pricing models discussed in Section III are instructive. When differential pricing is allowed, large retailers indeed obtain better overall pricing, the typical enforcement context in which revivalists most often seek to intervene. Yet, differential pricing reduces input and retail prices and raises welfare, results that counsel against intervention. Forms of non-linear pricing are commonly used in contracts between suppliers and large retailers and are central to the recent Robinson-Patman cases. Thus, models that incorporate non-linear pricing have a special relevance for the economic and antitrust analysis of intermediate good price discrimination and cases under the Act. As Carlton and Keating conclude, a “failure to account for the use of nonlinear pricing can lead to a mistaken antitrust analysis—especially when efficiencies are involved.” This is another important reason why the theoretical assumptions of Katz-type modeling and other models that analyze linear pricing may have little practical relevance for typical Robinson-Patman enforcement.

This section extends Section III’s analysis of how differential pricing with two-part tariffs increases welfare to the use of volume discounts, including the use of all-units discounts and rebates. Manufacturers often sell to retailers with non-linear pricing using volume discounts rather than two-part tariffs, and these contracts have generated antitrust scrutiny. While there is not, to our knowledge, an existing analysis that compares the welfare effects of uniform versus discriminatory input pricing when firms use volume discounts, it is well known that both two-part tariffs and volume discounts can produce similar Pareto-preferred allocative outcomes.

Specifically, both two-part tariffs and all-units quantity discounts promote efficient resource allocation and increase welfare by eliminating double marginalization. Kolay et al. (2004) show that, in the independent demand setting with complete information, efficient two-part tariffs and volume discounts can both be used to induce downstream retailers to expand output and lower retail price in a manner consistent with eliminating double marginalization. Eliminating the double margin results in a Pareto improvement for the wholesale firm, the retail firm, and consumers. The joint profits of the upstream and downstream firms are higher, the downstream price is lower, and output is higher, increasing consumer welfare. Given that the elimination of double marginalization (EDM) increases the joint profits of the upstream supplier and the downstream retailer, use of such contracts with non-linear pricing should be favored over linear pricing when double marginalization is a significant issue in a vertical contracting chain, as is likely for any branded product.

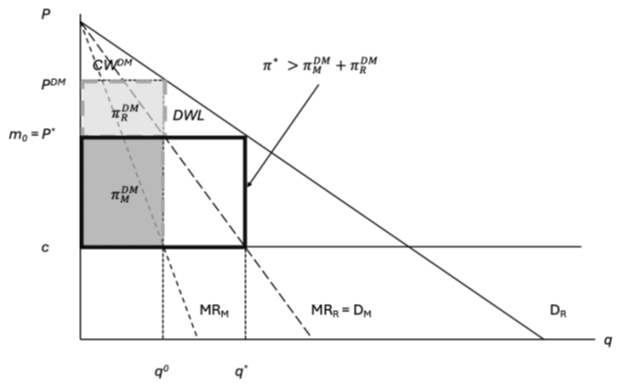

To illustrate these points, Figure 1 shows the double-marginalization problem and its solution with linear cost of production, no retailing cost, and linear independent demand. A vertically integrated manufacturer/retailer would set its price at P* and produce and sell q* units. Profits would be π* = (P* – c) q*. With an independent manufacturer and retailer, the manufacturer’s derived demand DM equals the marginal revenue curve (MR) of the consumer demand curve DR, and it will maximize profits by setting the input price m0 = P*. The retailer will take the input price m0 as the marginal cost of an input and set its optimal price at PDM > P*, resulting in q0 units sold. Profits for the manufacturer πMDM = (P* − c) q0 will be half of the vertically integrated profits, and the profits of the retailer are one-quarter of the vertically integrated profits πRDM = (PDM − P*) q0. Joint profits of the manufacturer and retailer fall and are three-quarters of the vertically integrated profits. Consumer welfare also falls relative to welfare with a vertically integrated manufacturer/retailer.

Figure 1 – The Effects of Double Marginalization

Thus, as Spengler noted in 1950, a vertical merger between the manufacturer and retailer in this setting would eliminate this double margin and reduce downstream prices, while increasing joint profits, output, and consumer welfare. The same would be true for any contractual solution that achieved the elimination of the double margin. As noted in Section III above, an efficient two-part tariff sets the input price at marginal cost c. The retailer then sets the downstream price equal to the joint profit maximizing price P*, eliminating double marginalization. The joint-maximized profits are divided by bargaining over the size of a lump sum fixed fee paid by the retailer.

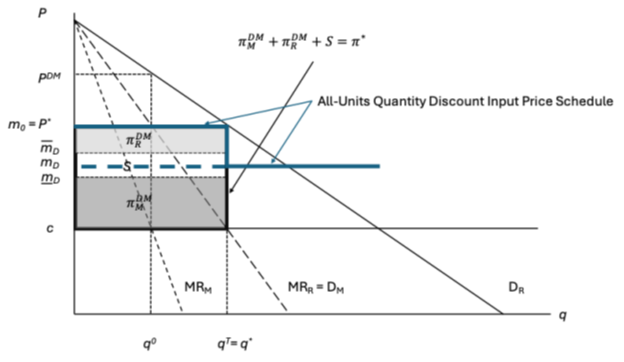

Kolay et al. show that use of all-units volume discounts can also achieve EDM in the independent demand complete information setting. Instead of selling the input at marginal cost, the seller specifies both a regular price m0 as well as a discounted price mD that is applied to all purchased units if the retailer’s input purchases equal or exceed a quantity threshold qT> 0. This non-linear price schedule is shown in Figure 2 where the quantity threshold is set at qT = q*. For purchase quantities below the threshold, the input price is m0, while for purchase quantities at or above the threshold, all units are priced at mD < m0. Because the discount applies to all purchased units, the marginal cost of a unit at the quantity threshold equals mD – (m0 -mD)qT. If the difference between the two prices and the threshold is large enough, over some range the retailer’s costs of purchasing q < qT units of the input will be greater than if he purchased q = qT units. This incentivizes the retailer to expand his output to meet the threshold. In effect, the all-units discount creates a discontinuity in both marginal costs and profits at the quantity threshold that incentivizes the retailer to expand output to the quantity threshold.

If the discounted input price is set so that m̄D ≤ mD ≤ m̲D, the retailer will choose to produce q* units of output. To sell qT units, the retailer must set his retail price at P*, which in turn eliminates the double margin. Joint profits increase by the area labeled S in Figure 2, and equal those of the vertically integrated manufacturer retailer. Output and consumer welfare also increase when the double margin is eliminated.

Figure 2 – All-Units Discount and EDM

While a formal demonstration of equilibrium in the interdependent demand case is beyond the scope of this short paper, if the upstream manufacturer is able to set the quantity threshold for each retailer at the output consistent with joint profit maximization, the manufacturer could duplicate the profits earned by a vertically integrated firm through the use of retailer-specific, tailored volume discounts. As illustrated in Figure 2, at qT = q* the retailer’s marginal revenue equals c, while his input cost will equal mD > c. As long as the amount of diversion from other downstream retailers is not large, a given retailer will not have any incentive to lower its downstream price to divert sales from other retailers. If this is the case, then the retailer with a threshold qT = q* will choose to price its output at P*.

It is also clear that both the quantity threshold, and the equilibrium range for the discounted input price can depend on the demand faced by a particular retailer, differences in the relative bargaining strength of a retailer, and the retailer’s marginal cost. Thus, differential thresholds and discounts for each retailer can result when they are permitted. The threat of antitrust action that forbids the use of discriminatory thresholds or discounts could result in manufacturers focusing such a program only towards the largest sellers, or adopting tiered schedules available to all that feature lower prices for those that meet larger quantity thresholds, thereby achieving EDM in an imperfect way. If this was the result, small retailers would face both higher input prices and the reduced profits from double marginalization, and larger retailers would imperfectly achieve EDM. Under such circumstances, any mandate for uniformity would reduce welfare.

V. Recent Empirical Research on Liquor Sales

As noted above, the Biden FTC, in a 3-2 vote, filed two Robinson-Patman cases. The first involved the use of differential input pricing by liquor wholesalers. While empirical evidence of the effect of regulating wholesale price discrimination is scarce, two recent papers have examined empirically the wholesale liquor industry and conducted simulations of the effect of a law that regulated the use of wholesale price discrimination. In the first, Hagemann (2018) simulates the effect of a ban on quantity discounts based on estimation of a structural model of the New York retail liquor market. While New York state does regulate alcohol pricing, it permits upstream firms to offer quantity discounts. Based on the demand and cost estimates generated from the estimation of his structural model with volume discounts, Hagemann simulates the effects of a policy that bans quantity discounts and finds that such a policy would reduce total welfare by 13 percent on average. Such a ban would lower wholesaler profits, and retailers that benefited from quantity discounts would face higher input costs and lower profits, while smaller retailers would benefit and face lower input costs. Because the largest retailers pass input cost increases onto consumers, he finds that the average retail price paid by consumers would increase under a ban.

In a second paper, Aslihan Asil produces the opposite results, predicting that discriminatory pricing causes an annual consumer welfare loss of $4.91 per individual, totaling $529 million annually. The Commission majority in FTC v. Southern Glazer’s cited her paper and its results to argue that recent empirical scholarship shows clear consumer benefits from Robinson-Patman enforcement.

In contrast to Hagemann’s approach, which simulated the short-term effects of a ban on quantity discounts, Asil estimates and simulates the longer-term effects of state-level Robinson-Patman-type laws. While Hagemann’s structural estimation and simulation assume the number of retailers operating in New York State would remain static after a ban on volume discounts, Asil focuses on the long-term changes to the number and type of retailers associated with state-level statutes.

The two papers differ in other important ways. Hagemann’s simulations are based upon the estimation of a structural model using panel data, while Asil’s econometric analysis and simulations are based on cross-sectional data and comparisons. Her econometric analysis uses reduced form cross-sectional regressions to examine state variation in laws regulating wholesale price discrimination. Asil’s regressions examine how liquor prices and the number of liquor store outlets differ between states that have passed Robinson-Patman-type statutes that regulate price discrimination at the wholesale level (RP states) and states that do not (UR states). The author estimates the state-level average chain and independent liquor store prices for spirits for different types of state liquor law regimes. She finds that chain store prices in UR states are lower than in RP states, while independent store prices in UR states are higher than in RP states. Using an equally weighted average of independent and chain store prices in a state, she estimates that average prices in UR states are higher than in RP states.

The author also uses separate cross-sectional data to estimate the average number of stores primarily selling packaged alcoholic beverages in urban counties. Cross-sectional regression analysis estimates the association between a measure of market structure (e.g., the number of stores or the share of independent stores based on outlets, employees, or sales) and the different types of state liquor law regimes. The author finds that urban counties in RP states have more outlets per capita and higher independent store shares than urban counties in UR states.

There are numerous drawbacks to the author’s approach. First, the paper uses a cross-sectional regression analysis to estimate the association between state regulation and her variables of interest, prices and the number of liquor store outlets, and then treats these estimates as causal effects in her policy discussion. While some cross-sectional approaches can produce useful evidence of associations that suggest causal effects, modern empirical economics recognizes that such cross-sectional estimates generally are not evidence of causation. Cross-sectional estimates often cannot identify the causal effects of regulations because of the difficulty of controlling effectively for omitted covariates (such as pre-existing and uncontrolled-for differences between the states) whose effects would be embedded in the estimated regression coefficients. For these reasons, causal inferences from such estimates are viewed skeptically.

Modern empirical economics instead favors the use of causal research designs, such as difference-in-difference event studies that use panel data to measure the causal effect of changes to regulation in treated states relative to control states. These studies isolate the causal effect of regulations by comparing the change in variables of interest in the regulating state or states (e.g., prices) before and after the regulation to the before and after difference in a control group of states. Such modern approaches cannot be done using cross-sectional data and instead require the collection of panel data (cross-sectional data collected repeatedly over time). Although other studies of liquor markets have done so, the Asil paper does not use the differences-in-difference approach.

Beyond not using the preferred techniques of modern empirical economics, specific reasons exist to reject causal inferences from the paper’s cross-sectional regression analyses. The author’s key variable of interest is whether or not a state has passed a Robinson-Patman-like statute that regulates intermediate good price discrimination. Yet, the relevant statutes are decades old and the author’s cross-sectional approach does not properly control for reverse causality (states with more independent retailers are more likely to pass such state statutes) and other pre-existing or changing differences between the states that affect alcohol prices. Moreover, the author’s cross-sectional analysis does not control for many other potential omitted covariates, including state level or private enforcement rates that can occur under the federal Act, a state version, or both. For decades before the Biden Administration, FTC leaders rejected the Biden and current FTC’s enthusiasm for enforcing the Act. At the federal level, the argument is thus about levels of enforcement, not whether the law exists. The same could be true at the state level, and the author ignores possible enforcement differences among the states, assuming there are none if the state merely has a statute. Moreover, the Robinson-Patman Act is still a federal statute, enforceable also through private actions, which can be filed in states that do not regulate intermediate good price discrimination at the state level. Thus, in theory, enforcement under the federal Robinson-Patman Act can reach firms in these states.

The paper has other drawbacks. The author’s per capita measures of structural competition based on store counts, number of employees, and sales in urban counties poorly reflect the effects of a state level Robinson-Patman-type regulation on actual competition. As noted above, the estimated cross-sectional relationships are associational and not causal. Even if they were causal, it is far from clear that relevant geographic antitrust markets coincide with counties, and antitrust markets would likely include liquor sales through outlets that Asil ignores. Indeed, the author’s description of consumer choice in the paper suggests relevant antitrust geographic markets that would be much narrower than urban counties. Moreover, the study presents no direct evidence that shows that the number of stores in a county is linked to harm to competition or prices. Thus, the study falls short of demonstrating that competition or prices in properly constituted antitrust markets were adversely affected because of wholesale price discrimination.

Finally, the validity of the paper’s simulation of the welfare effects of a ban depends on the inputs and data used to calibrate the parameters of the demand and cost functions, as well as the realism of the model. The calibration relies on matching the model’s parameters to cross-sectional averages from RP states and UR states to simulate what would happen if UR states became RP states. As with the author’s regression analyses, for many of the same reasons discussed above, these differences do not measure the causal average effect of changing UR states into RP states.

The model used in the calibration also depends on other unrealistic assumptions. The welfare calculation assumes that, ceteris paribus, all consumers prefer to purchase at independent stores because they are more convenient; i.e., the convenience parameter in the indirect utility function for the independent store is greater for every consumer. As a result, for some customers, the move from the independent store under higher RP prices to a chain store at lower UR prices results in a decrease in consumer surplus. Such an assumption is unrealistic. For example, for consumers who buy their alcohol with other items at a chain store, greater convenience would appear to be at the chain store, not elsewhere. And changes to this assumption would certainly reduce, and in some circumstances reverse, the predicted welfare gains from the passage of Robinson-Patman-type legislation.

VI. Conclusion

Katz’s well-known 1987 article began: “I come to exhume Robinson-Patman, not to praise it.” Over the following decades, economists have replaced economically incoherent arguments with internally consistent theoretical models that show that it is possible that intermediate good price discrimination can decrease welfare. Nevertheless, the literature has been much less successful in providing theoretical guidance or empirical evidence on whether and when these possibility theorems apply to potential real-world cases outside of the academic blackboard. When models instead incorporate key institutional features of pricing that large firms actually use, such as non-linear pricing and bargaining, economic analyses find that regulating intermediate good price discrimination increases input prices and reduces welfare.

The lack of useful guidance from models suggesting potential harm is particularly relevant when one considers the history and content of Robinson-Patman. The Biden administration’s attempts to revive the Act have not ended under the Trump administration. The latter’s dismissal of the FTC’s case against Pepsi, while continuing the case involving liquor, may suggest that the current administration could attempt to “target” cases where intermediate price discrimination causes competitive or direct consumer harm. Nevertheless, like the economic literature, neither the statute nor the existing case law provides useful guidance for enforcing the statute consistent with modern antitrust principles. Indeed, the Act’s history shows instead that enforcement had little purpose other than to constrain innovation in manufacturing and retailing by large, efficient firms.

While enforcement that is “targeted” towards harmful discriminatory input pricing sounds useful in theory, it is hard to see how this could work in practice. Moreover, many revivalists, hostile to modern economic analysis, reject the obvious: today’s retailers have succeeded because they satisfy consumer desires better than their competitors, including smaller ones. To the extent revivalists advance economic theories, many push the incoherent propositions of the New York Times op-ed discussed at the beginning of this essay.

For any harms the revivalists or modern economics suggest from discriminatory prices, antitrust law already has ample ability to apply a nuanced policy that considers both the benefits and costs of challenged practices under existing Sherman and Clayton Act precedent. Thus, there is little marginal benefit from reviving the Act, a statute ill-suited to such a task. Rather than working on exhuming Robinson-Patman, perhaps we should all seek shovels to bury it for good.