Costs of Regulatory Takings and Property Value Destruction

This post is part of a series on “Rule of Flaw and the Costs of Coercion: Charting Undisclosed Burdens of the Administrative State,” and comprises one element of A Brief Outline of Undisclosed Costs of Regulation.

[The 1973 Council on Environmental Quality book, “The Taking Issue,”] could well turn around the thinking of people of practical affairs—attorneys, government regulators, legislators, judges and, with luck, maybe a few landowners—most all of whom are perpetuators, witting or unwitting, of the cherished American myth of “just compensation.” This myth holds that the Constitution guarantees every landowner the right to do whatever he pleases with his land and that when government significantly interferes with that right (certainly when the interference goes so far as to remove any chance of selling the land for a profit), government must remunerate the landowner for having “taken” his property….The authors are out to slay that myth.

—1974 law review article reviewing “The Taking Issue,” a book-length report commissioned by the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ)

From classical liberal and individual rights perspectives, the administrative state is inherently an affront to liberty. As rule-of-law frameworks that safeguard liberty go, none rival property rights, “the guardian of every other right,” in importance (see James W. Ely Jr., “The Guardian of Every Other Right: A Constitutional History of Property Rights,” New York: Oxford University Press, 1998).

Among many protections, the Constitution’s takings clause affirms, “private property [shall not] be taken for public use, without just compensation.” Safeguards to avoid uncompensated or ill-compensated takings are unmentioned in the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) Circular A-4 guidance to agencies on performing regulatory assessments. Nor is there treatment of loss of property rights or value loss as regulatory costs in the annual OMB “Report to Congress” on regulatory costs and benefits.

Property is mentioned in Circular A-4, but in the context of discussing externalities and public goods, and market-socialist property-reassignment schemes to achieve government’s ends, such as:

…fees, penalties, subsidies, marketable permits or offsets, changes in liability or property rights (including policies that alter the incentives of insurers and insured parties), and required bonds, insurance or warranties.

The Circular A-4 stance that “distributional effects” or transfers matter disregards takings of property—the most elemental (re)distribution.

Takings issues noted here are just the beginning of government neglect of the institution of private property, notable especially in emergent sectors. But the disdain for compensation is a feature, rather than a bug, of the administrative state. The very point of regulatory takings, as distinct from an outright seizure, is to circumvent and hide costs. A modern example is a Supreme Court case regarding agencies’ generous designation of private land as “critical habitat,” for species (a frog in this case), even if the species in question did not exist there, and would require costly conversion of the land from its current state to attract it.

One of the developments that helped achieve this warlike state of affairs (one in which landowners are punished rather than incentivized) was described to me by Robert J. (“R. J.”) Smith, Distinguished Fellow at the Competitive Enterprise Institute. The Council on Environmental Quality (or CEQ, formed under Nixon in 1969) commissioned two classic and paradigm-changing books, as R.J. described them: “The Quiet Revolution in Land Use Control” and “The Taking Issue: A Study of the Constitutional Limits of Governmental Authority to Regulate the Use of Privately-Owned Land Without Paying Compensation to the Owners.”

These reports effectively argued that it would cost the nation far too much to pay for all the land that was necessary to preserve and protect the environment. Therefore, a vast expansion of the use of regulatory takings was needed, such that takings would become so commonplace and routine that they would be viewed as an expansion, and necessary use, of the police powers, like speed limits.

Legal theorists in the Progressive and New Deal eras, of course, had long since been working to deconstruct the property protections that the Framers had created. It was not a surprise, then, for the nearly brand-new CEQ to push that effort further and attempt to remake the Founders’ republic by means of a report that argued for vast new programs of property seizure.

After all, prior and contemporary environmental legislation like the Clean Air Act (1970), the Clean Water Act (1972) and Endangered Species Act (1973), and subsequent amendment and interpretation, followed this new philosophy: no need for condemnation, no need for compensation, and no need for purchase. The government may, and should, simply regulate whatever it wants left unused, as R.J. put it.

“The Quiet Revolution” set about redefining the “very concept of the term ‘land.’…‘Land’ means something quite different to us now than it meant to our grandfather’s generation….Basically we are drawing away from the 19th century idea that land’s only function is to enable its owner to make money” (p. 314).

Celebration ensued. As the 1974 law review salute put it, “If the courts at the same time begin to apply some of the analysis of ‘The Taking Issue’ and uphold land regulations on the same basis as other police power regulations, then together the legislatures and the courts will have at last slain the American myth of just compensation.”

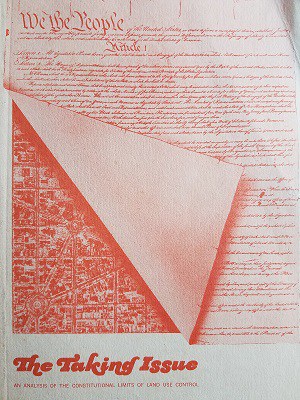

The arrogance seems captured by the cover of the book, with an image of the Bill of Rights dog-eared to show a map underneath.

Critics weighed in in the 1980s, defending the reality of the pains of inverse condemnation. The debate continues today: For example, a Touro Law Review 40-year anniversary symposium on “The Taking Issue” took place in 2014 (“Still an Issue: The Taking Issue at 40”). Among the proceedings, Richard A. Epstein weighed in on “The Common Law Foundations of the Takings Clause: The Disconnect Between Public and Private Law.”

Debates continues over “the widely disputed issue of whether Takings Clause protects against regulatory takings,” and into whether regulatory takings doctrine should be “reconsidered from the ground up.” Cost estimates do not happen, but costs are genuine to those affected. It would be refreshing for scholastic fervor to seek to expand liberty rather than look for workarounds favoring greater government power.