The Fall 2022 Unified Agenda of Federal Regulations Extends “Whole-of-Government” Activism

Photo Credit: Getty

The genius of the Progressives in the late 19th century was to preempt or push large sectors of the emerging future (the environment, schools, electromagnetic spectrum, infrastructure, welfare, the medical world) into the political world.

—Fred L. Smith Jr.

Federal departments and agencies are supposed to highlight regulatory priorities in the twice-yearly Unified Agenda of Federal Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions. Well, almost twice-yearly. The Biden administration just released the Fall 2022 edition a few months late, on January 4—the latest since the Obama administration blew off the Spring 2012 edition entirely.

The little-known Unified Agenda presents a freeze-frame of active and longer-term rules at various states of urgency moving through the pipeline, along with a selection of rules recently finalized. It’s envisioned as “a way to share with the public how the themes of equity, prosperity and public health cut across everything we do to improve the lives of the American people.” Each semiannual update is important because priorities can change dramatically following an election or a shift in political motives.

This latest Unified Agenda reveals an overall picture of the Biden administration’s “Modernizing Regulatory Review” campaign transforming the function of the White House Office of Management and Budget’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) from a supervisory one to advancing “net benefits” as the progressive wing of the Democratic party sees them. In the latest Agenda, it’s not that total rule counts are atypical. It’s that President Biden appears to be ramping up economically significant regulations to the pre-Trump heights of Obama and Bush (and likely beyond).

The terse preamble, albeit containing less text and philosophical zeal on “building back better” than the previous three editions of the Biden-era Agenda, informs readers that administration will “continue delivering on the President’s agenda to advance economic prosperity and equity, tackle the climate crisis, advance public health, and much more.”

What does that mean? One finds these aims amount to a series of top-down economic and social pursuits advancing “Whole-of-Government” campaigns. The preamble also refers to cues it is taking from new legislation like the Infrastructure Law, the Inflation Reduction Act, and the CHIPS and Science Act. These bills are hyper-regulatory in nature even before the first rule gets written, so one can expect additional rule flows in forthcoming editions of the Unified Agenda, as there hasn’t been enough time yet for these gargantuan new laws to make their prolific rulemaking offspring known.

Biden’s Unified Agenda must also be viewed in the context of his January 2021 “Modernizing Regulatory Review” declaring the regulatory streamlining program of the former Trump administration. Sweeping revocations were issued, including even a day-one directive removing guidance document portals. Policy making by guidance does not get captured in the Unified Agenda, the White House Report to Congress on federal regulation, or the Federal Register.

Last years’ spring edition tossed out the observation that “[T]he Unified Regulatory Agenda continues rolling back the obstacles to recovery, equity, and sustainability that the prior Administration put in place.” Mere months earlier under Trump, this very same OIRA was engaged in a regulatory cost freeze and removing two rules for each significant one added. Before, OIRA had a firm oversight role. Now, the office has essentially been reassigned from evaluating the cost/benefit ratio of regulations to advancing Biden’s Whole-of-Government political/social agenda.

The flip-flopping mission at OIRA is one of the reasons it can no longer perform its oversight role and needs to be replaced. No one should want an executive branch that uses every lever available to unilaterally carry out its own controversial agenda in a way that excludes the elected Congress.

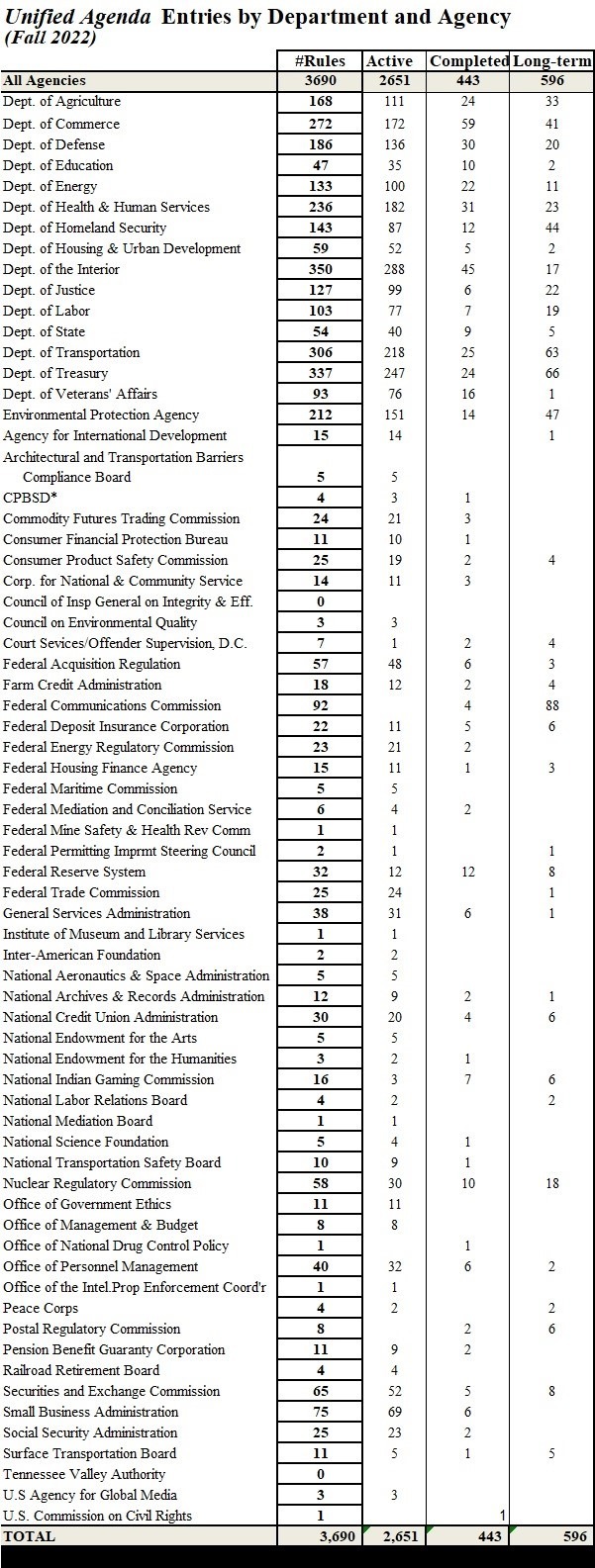

Digging into the specifics of the Fall 2022 report, the regulation pipeline breaks down a cross-section of rules from over 60 federal departments, agencies, and commissions this way:

- Active Actions: Pre-rule actions; proposed and final rules anticipated or prioritized for the near future;

- Completed Actions: Actions completed during approximately the previous six months; and

- Long-term Actions: Anticipated longer-term rulemakings beyond 12 months. Under some administrations, presenting more speculative longer-term rules is encouraged, other times not.

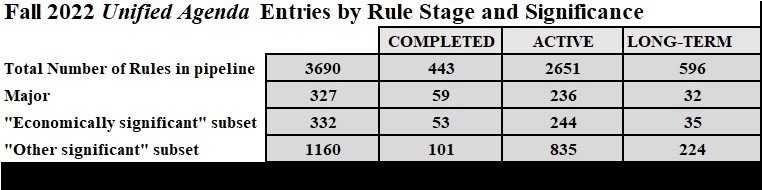

The Fall 2022 Unified Agenda of Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions finds 69 federal agencies, departments, and commissions floating 3,690 rules and regulations at these stages compared to 3,777 a year earlier. Trump’s counts were comparable but with a big difference; hundreds of rules in each Agenda were designated “Deregulatory,” a category deleted by Biden in another blow to disclosure, yielding a lower “net.”

Rules appearing in the Unified Agenda can get mired at the same stage for years, or they may reappear in subsequent editions at later stages before dropping off after completion. In fall 2022, 386 of the Active actions are appearing for the first time, a drop from previous editions. Agencies’ regulatory activities, however, are not constrained to what they publish in the Agenda unless an administration were to explicitly require it, and guidance documents are not covered in the Agenda at all.

As might be expected, a relative handful of executive branch agencies each year account for the greatest number of the rules in the pipeline. In the Biden Agenda, the Departments of the Interior, Transportation, Treasury, Commerce and Health and Human Services are the most active. These top five, with 1,501 rules among them, account for 41 percent of the 3,690 rules in the Unified Agenda pipeline at the moment. The Environmental Protection Agency, with 212 rules, comes in sixth. The Federal Communications Commission, with 96 rules, leads the pack among independent agencies.

A subset of the Agenda’s rules are designated “economically significant,” meaning they carry estimated annual economic effects of at least $100 million. Sometimes an economically significant rule is intended to reduce costs, but the political response to the pandemic bequeathed unprecedented spending and an ample supply of new rules, even under Trump. One prominent example was the creation of the Paycheck Protection Program to aid businesses, with dozens of economically significant rules related to it—but they were designated neither regulatory nor deregulatory per the Trump-era nomenclature.

The new Biden Agenda contains 332 economically significant rules compared to 295 a year ago. Generally, at least 1,000 additional rules are deemed “other significant” in each edition of the Agenda no matter who’s boss, and those should not be ignored.

With declarations to showcase rules to “Protect the Public from COVID,” “Combat Housing Discrimination,” “Tackle the Climate Crisis,” and to “Improve Pipeline Safety and Environmental Standards,” clearly there is little self-awareness about government controls that create problems for that same government to now solve with more regulation.

In reality, property rights and markets are indispensable for achieving all sound policy goals. But rarely is that mentioned, as illustrated by OIRA’s showcasing of the EPA’s “Transitioning Toward Zero-Emission Technologies” to “strengthen greenhouse gas emission standards for light- and heavy-duty vehicles.” This substitutes one fossil-fuel powered vehicle type for another and will replace government-induced fuel shortages of today with rare-earth mineral shortage and crises tomorrow.

As it stands, OIRA has flipped from carrying out Trump’s now-revoked “one-in, two-out” executive order on “Reducing Regulation and Controlling Regulatory Costs” to praising government’s own mandates. This implies that OIRA may not be salvageable as an oversight body. Even should there be future regulatory pauses, we’d later find ourselves back at square one with a series of executive orders turbocharging the regulatory state.

The writing was on the wall even under Trump, when the longer-term “Deregulatory” category of economically significant rules was outnumbered by the regulatory ones. The “Deregulatory” designation for a federal rule not only no longer exists under Biden, the label was retroactively scrubbed from the government’s database (a phenomenon echoed in the disappearance from OMB’s website of draft editions of the Report to Congress on regulations required by the Regulatory Right-to-Know Act).

If OIRA is finished as a regulatory oversight body, a future Congress can replace it with both an actual oversight body plus an “Office of No,” chartered with placing the escalation of economic, social and environmental well-being back in the realm of competitive rather than political discipline.

Tracking the scope of government will increasingly pose a challenge, as the Unified Agenda and other official disclosures fall short as adequate yardsticks for disclosure and measurement of government. The new 118th Congress should start with a series of exploratory hearings and the laying of legislative groundwork for emergency reforms and restoration of Article I lawmaking rather than agency activism.