Wishful Thinking Is No Way to Address Public Pension Shortfalls

More state revenue but less money for public services?

More state revenue but less money for public services?

That’s the situation in which states with large unfunded pension obligations can find themselves if they don’t take significant steps to address those shortfalls. And that situation, bad as it is, could quickly get worse.

California Governor Jerry Brown’s revised budget for 2018-2019 projects revenues will be 30 percent greater than 10 years ago, but less money will be available for public services.

The reason? What David Crane, a lecturer at Stanford University and president of the advocacy group Govern for California, calls the “Big Three” threats to the state budget: 1) pension costs, 2) health insurance subsidies for retired state employees, and 3) Medi-Cal, the health insurer for lower income Californians.

To address the pension shortfall, Crane calls on the state to “suspend annual benefit increases for retirees until pension funds are adequately funded and reduce accrual rates for years not yet worked by existing employees.” Reform, he notes, is urgent:

Absent reform, the “Big Three” will consume ever-larger shares of the budget and lead to ever-more-frequent calls for tax increases that won’t produce new or improved services.

That’s bad enough, but the situation could quickly worsen in the event of a market downturn:

And the pressure for more taxes could quickly worsen. That’s because California’s tax revenues are correlated with investment markets. The next bear market, Gov. Brown predicts, will reduce annual revenues by more than $20 billion per year.

The fiscal pain is already being felt in Palo Alto, which is seeking to cut $4 million from its proposed 2019 budget.

To its credit, though, the Palo Alto City Council’s Finance Committee called for the cuts after revising down the state’s pension return projections. Palo Alto Online’s Gennady Sheyner reports:

Last year, the Finance Committee commissioned an actuarial study to assess the city’s liability should the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) reduce its expected rate of return (known as the “discount rate”) from its existing projection of 7 percent to 6.2 percent, a rate its own consultant deemed more realistic. The change would add roughly $8 million to the city’s short-term costs, the analysis found.

Those few percentage points may not seem like much, but they can make a big difference. Yet, state pension plans often make overly optimistic projections that can worsen funding shortfalls when they fail to materialize.

Bloomberg columnist Barry Ritholtz highlights the riskiness of such an approach:

[R]egardless of what your risk-adjusted return expectations are, the first rule of economics cannot be denied: There is no free lunch.

I was reminded of this by a report that the League of California Cities wanted the state’s big public pension fund, CalPERS, to boost investment returns. However, I did a double-take when I read the following.

The legislative representative to the League of California Cities urged the CalPERS Investment Committee Monday to think “out of the box” in finding a way to exceed its 7% investment return projections, saying that cities won’t be able to pay their monthly contributions to the pension plan if returns are that low.

There is so much wrong with this statement, so much at odds with the body of knowledge investors have painfully amassed over decades, that my first reaction was that I must have misunderstood it.

Yet, that statement does accomplish one thing: it illustrates public pension plans’ propensity to overpromise and then try to find out how to deliver.

“Those who declare that they want higher returns must also recognize that they are also implying a willingness to risk lower returns to get them,” notes Ritholtz, who adds, “of all the things returns are based upon, they are never dependent upon what you need or desire.”

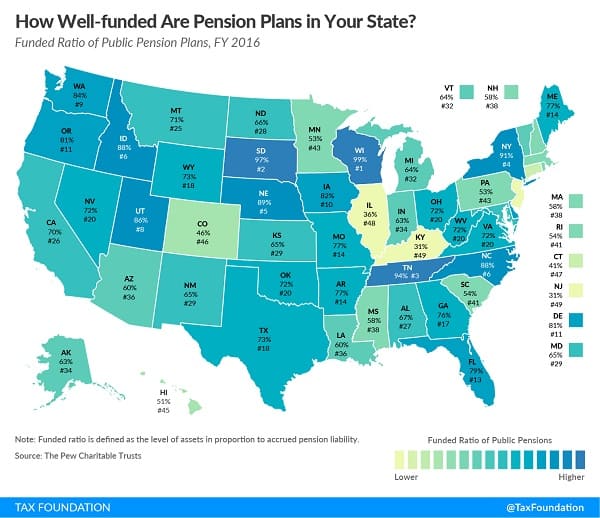

For those interested in how their state is doing in terms of public pension funding, the Tax Foundation recently issued a map showing funding levels across the nation.

The map is based on data from the Pew Charitable Trusts, which estimates $1.4 trillion in total unfunded pension liabilities nationally. However, that estimate could be considered conservative, for the reasons Ritholtz describes. As the Pew report explains:

Preliminary information for 2017 indicates that the year’s strong investment performance will decrease reported unfunded liabilities, as public pension funds—which continue to allocate an ever greater share of assets to complex investments such as equities, hedge funds, real estate, and commodities that can produce higher returns than other assets but may also expose plans to increased risk—experienced gains from the upswing in financial markets. However, that same market volatility could have an adverse impact in the long term, especially if lawmakers also fail to make adequate annual contributions to state plans.

Even small changes to projected returns can significantly increase liabilities. Pew applied a 6.5 percent return assumption, instead of the median assumption of 7.5 percent, to estimate the total liability for state pension plans and found that it would increase to $4.4 trillion—$382 billion more than the current amount. The funding gap would then jump to $1.7 trillion.

Of course, politicians don’t have much incentive to assume lower rates of return on pension fund investments, as that would require them to commit higher levels of funding for pensions. That leaves them with less money to pay for spending on popular programs. But now that pension bills are coming due, they’re being left without much of that money anyway.

For more on public sector unions, see here. For more on public pensions, see here.