Aloha Approvals

Surfing the Hawaii permitting bureaucracy

Hawaii’s permitting system is at a critical juncture, faced with the dual challenges of rebuilding in the wake of the 2023 Maui wildfires and addressing a severe housing shortage. Delays and inefficiencies of the current system have hindered recovery efforts and more affordable housing. This report explores lessons learned from Hawaii’s recent experimentation with permitting reform and identifies other states that are streamlining permitting through third-party review systems. Hawaii can make its system of third-party review permanent while avoiding some predictable pitfalls. It can also build upon its existing automatic approvals law. Hawaii has the opportunity to establish an accountable permitting system that meets the state’s unique cultural and environmental priorities.

The Lahaina problem

In August 2023, Hawaii faced one of the most devastating natural disasters in its history when a series of wildfires swept across the state, with Maui bearing the overwhelming brunt of the destruction. These fires, fueled by unusually dry conditions and powerful winds from Hurricane Dora, burned over 6,600 acres of land in Maui and left behind a trail of unprecedented destruction. The historic town of Lahaina was the hardest hit, with over 2,200 structures damaged or destroyed and the loss of more than 100 lives, making this the deadliest wildfire in the United States in over a century. Thousands of residents were displaced, with some ending up in shelters. Many were forced to flee on foot or dive into the ocean to escape the encroaching flames.

The scale of the devastation brought longstanding vulnerabilities to light. Decades of unmanaged land, overgrown with invasive grasses, had created a tinderbox for such fires. Compounding the risk were systemic challenges in water management and infrastructure. Firefighters were left without adequate resources to combat the fast-moving blazes.

The wildfires not only revealed problems in Hawaii’s land and resource management but also exposed critical weaknesses in permitting processes that delayed efforts to rebuild affected communities. The slow pace of building reviews and zoning approvals has long been a barrier to development. After the fires, these challenges have taken on new urgency.

Gov. Green’s permitting emergency order

Even prior to the wildfires, Hawaii’s housing problems were so acute they were deemed an emergency. In July of 2023, a month before the fires, Gov. Josh Green issued an emergency order to streamline the state’s permitting processes. The “Emergency Proclamation Relating to Housing” invoked the governor’s emergency powers to suspend several state and county laws and regulations, including environmental reviews, historic preservation laws, and zoning rules. The goal was to fast-track the construction of 50,000 housing units within five years.

A key provision of the order was the creation of the Build Beyond Barriers Working Group, a 22-member body tasked with coordinating and expediting housing approvals. The group was empowered to replace traditional regulatory bodies in reviewing and approving projects, effectively centralizing decision-making under a single housing officer. Additionally, the order allowed for the conversion of office buildings into residential units and removed requirements for county council approvals for some affordable housing projects. While Green framed the proclamation as necessary to address an existential emergency, the sweeping nature of the reforms sparked significant controversy.

Pushback and criticism

The emergency proclamation faced immediate pushback from environmental and cultural preservation groups, including the Sierra Club and Native Hawaiian organizations. Critics argued that suspending laws such as Hawaii’s environmental review statutes and protections for culturally significant sites risked causing irreparable harm to natural and cultural resources. A potential lack of transparency in the Build Beyond Barriers Working Group, which was not subject to Hawaii’s Sunshine Law, also led to concerns about accountability. Some opponents accused the governor’s executive order of prioritizing development at the expense of long-standing safeguards, describing it as an overreach akin to “dictatorship.”

Lawsuits were soon filed. Motions claimed that the proclamation endangered Native Hawaiian burial sites and violated procedural norms. Adding to the troubles, the Build Beyond Barriers Working Group’s first meeting was held just a few days after the wildfires. At the meeting, emotions ran hot, public outcry intensified, and eventually Nani Medeiros, the state’s housing officer and head of the Build Beyond Barriers Working Group, resigned over threats against her and her family.

Some of the concern may have stemmed from a belief that the governor would hand over rebuilding of Lahaina to private developers. Regardless, the backlash made clear that even if the housing crisis was urgent, the process of addressing it required a delicate approach.

The replacement order

In September 2023, about a month after the wildfires, Green issued a revised proclamation that rolled back many of the original emergency order’s most contentious elements. The new proclamation reinstated some of the environmental review requirements, historic preservation laws, zoning requirements, and open meetings laws, signaling a retreat from the sweeping deregulation of the initial order. The Build Beyond Barriers Working Group was reorganized, shifting decision-making authority to a smaller team of state housing officials. Most importantly, Lahaina, which had been devastated by the August wildfires, was explicitly excluded from the proclamation due to its uniquely sensitive cultural and environmental concerns.

Despite these revisions, the replacement order maintained certain deregulatory elements, such as waivers from local development regulations, impact fees, and collective bargaining agreements to expedite hiring for permitting-related work. The revised proclamation reflected an attempt to balance the need for housing with respect for environmental and cultural preservation. It also left lingering questions about whether the reforms would be sufficient to address Hawaii’s housing problems.

Lessons learned

Green’s emergency orders underscore the challenges of addressing systemic housing shortfalls. The initial order’s more aggressive approach responded to the urgency of the housing crisis but revealed the risks of sidelining stakeholder concerns. The subsequent replacement order was an effort to reconcile these tensions, though the long-term effectiveness of that approach is uncertain. Hawaii learned that if it wants to find ways to streamline permitting, it must do so in a manner that does not lead to the substantial backlash observed with Green’s original emergency order.

Housing woes

The Hawaii wildfires destroyed over 2,000 homes, yet 18 months later only three homes had been fully rebuilt, illustrating the anemic pace of recovery. While approximately 228 rebuilding permits had been issued by January 2025, the process remains fraught with bottlenecks, including time-consuming reviews and overlapping regulations.

The situation highlights the difficulty of navigating Hawaii’s strict land use rules. Hawaii has the most restrictive land use regulations in the country and is notorious for its housing unaffordability. Traditional permit applications add up to twelve months to complete, even for relatively straightforward projects. These challenges are exacerbated by Hawaii’s comprehensive building regulations, which, while designed to enhance resilience against natural disasters, significantly increase construction costs and complicate the approval process.

For properties in sensitive areas, such as those near the coastline or in historic districts, permitting is even slower, as additional reviews are required to ensure compliance with zoning and environmental protections. These delays stall reconstruction. Delays also heighten the financial and emotional burdens on displaced residents.

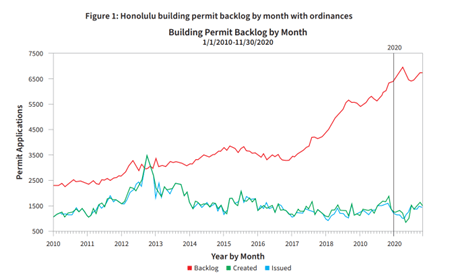

Hawaii’s permit problems extend beyond state-level regulations to the county level. Take, for example, Honolulu’s building permit backlog, which was increasing for years. In 2010, there was a backlog of 2,500 permit applications, which grew to approximately 7,000 by 2020. By 2022, the number had surged to nearly 12,000 pending applications. This growing backlog has corresponded with an increase in county ordinances (see figure 1). As of November 2022, the median processing time for residential permits was 330 days, while commercial projects had a median wait time of 420 days. By the end of 2024, the department began utilizing technology to reduce backlogs, bringing the permit backlog down to below 10,000.

Figure 1: Honolulu building permit backlog by month with ordinances

Despite the modest progress, Hawaii also continues to make unforced errors with respect to its building permits. Agencies in Hawaii are now required by both state statute and a recent executive order from Gov. Green to prioritize renewable energy permits, expediting solar approvals in pursuit of the state’s 100 percent renewable electricity production goals. This emphasis on solar permitting may be contributing to slower processing times for other types of building permits as these get pushed to the back of the line.

A novel approach

In response to these challenges, Hawaii has begun implementing targeted reforms to expedite the permitting process. One initiative is the establishment of the Recovery Permitting Center, operated by 4LEAF, Inc., a professional development services firm specializing in post-disaster recovery. The first center, which opened in Kahului in April 2024, streamlines the permitting process for homeowners in wildfire-affected areas, offering an expedited pathway for issuance of disaster recovery permits. A satellite office in Lahaina was subsequently opened to expand capacity and staff.

These offices focus on providing assistance navigating the permitting process for construction activities. Permit technicians work closely with applicants to address common issues early in the process. The company emphasizes direct engagement with homeowners, offering pre-application meetings to clarify requirements and resolve potential conflicts before plans are submitted. 4LEAF also provides on-site inspections for building, plumbing and electrical services.

The 4LEAF model shows evidence it can accelerate approval timelines. Maui County typically takes around 200 days to approve permits, whereas 4Leaf has processed them in an average of just over 73 days. Disaster recovery permits—one requirement for many project approvals—can now be processed within 15 business days if all required documents are in order.

By outsourcing elements of the review process to a third-party firm with expertise in disaster recovery, Maui County has created a more agile system capable of responding to its urgent needs. While early results from the 4LEAF initiative suggest promising outcomes, the overall success of reforms will depend on their scalability and the extent to which they can address the systemic issues related to backlogs and regulatory complexity that preceded the wildfires.

Currently, 4LEAF’s involvement in Maui’s permitting process appears to be a temporary reform, focused specifically on addressing the urgent needs of wildfire recovery. Yet, despite 4LEAF’s role in recovery efforts, it or similar contractors is not mentioned in Lahaina’s Long Term Recovery Plan. This is notable given that the plan specifically identifies permitting as a potential roadblock to some recovery projects.

Needed: Permanent third-party permitting

4LEAF’s model highlights the benefits of outsourcing elements of permitting to third-party experts. A promising avenue for improving Hawaii’s permitting process is to institutionalize and expand the use of third-party reviewers for permit applications. This approach has gained some traction in several other states already, including Tennessee, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. By learning from these examples, Hawaii might be able to improve on and make permanent its own third-party permitting system. Of course, Hawaii should also pay heed to past experiments with third party reviewers that did not work out as intended.

State-level reforms: Tennessee recently enacted a law allowing developers to engage third-party inspectors for building plans and inspections. Under the law, individuals and businesses are authorized to consult third party reviewers for certain local building, sewage system and wetlands inspections. Third-party reviewers must be registered with the state and certified by relevant professional associations, ensuring they meet stringent standards before performing inspections or certifying compliance. Local jurisdictions are required to respond to any submitted applications involving third-party reviewers within 10 business days; otherwise, applicants can receive a full refund of their application fees and seek approval through the state fire marshal’s office. Local agencies as well as the state fire marshal’s office maintain an oversight role, creating a dual accountability mechanism to ensure third-party reviewers have the right incentives. Additionally, the law includes substantial provisions related to conflicts of interest for inspectors, thereby addressing concerns about maintaining safety standards.

Louisiana has implemented expedited permitting processes that complement third-party reviewer systems. Louisiana’s expedited permit program allows applicants to pay additional fees for prioritized reviews, funding the pay for overtime for civil service employees or for hiring of third-party contractors to review permit applications. To date, there do not appear to be any significant implementation issues with the expedited process. In fact, as of 2011, over 30 percent of state air program permit applications were opting for this process, resulting in a 60 percent reduction in average processing time. Expedited permit reviews for oil and gas wells and pipelines reduced review times from 300 to 60 processing days.

Pennsylvania offers another compelling model with its Streamlining Permits for Economic Expansion and Development program. This initiative allows qualified third-party professionals to conduct initial reviews of certain permit applications. The program includes safeguards, such as state oversight of the reviewers’ recommendations, to maintain quality control. Applicants benefit from faster approvals, while state agencies retain ultimate authority over final decisions.

Virginia’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) employs a similar approach with its certification program for several of its environmental permits. For the DEQ’s Stormwater Management and Erosion and Sediment Control Plans, an expedited process is followed when plans are prepared, signed, and stamped by a Virginia-licensed professional engineer.

Notes of caution: Hawaii’s past experiences with third-party permitting review reveal some potential risks if these reforms are not properly implemented. A 2022 audit of the Honolulu Department of Planning and Permitting (DPP) found that many permits issued through a third-party review system were deficient, with nearly two-thirds of applications failing independent review upon reexamination. A lack of oversight was traced back to a 2018 policy shift under then-Mayor Kirk Caldwell, which allowed third-party-approved permits to be accepted without city verification.

Separately, a 2020 audit of DPP’s permitting processes found that third-party reviewers were not always faster than traditional reviews, with many applications requiring multiple resubmissions, ultimately slowing the process rather than expediting it. Weaknesses in oversight allowed certain private companies to exploit the system, bypassing appointment limits and undermining fairness in the review process.

Honolulu’s effort to streamline permit approvals through a one-stop shop office contributed to some of these challenges. While the intention was to consolidate reviews in a single office for efficiency, the office seems to have created a single bottleneck for permits, and a substantial county backlog. The lesson here is to adequately staff and resource centralized offices for effective permit processing.

In general, a system like Pennsylvania’s, where state agencies hold ultimate authority over final decisions, may make the most sense to avoid quality control issues. It is also important that third party reviews are not duplicative of agency reviews, thereby creating unnecessary redundancies. A system of expedited permitting, like Louisiana’s, can be effective so long as fees pay for highly qualified reviewers.

Building on Hawaii’s automatic approvals law

Hawaii already has a framework for accelerating approvals through its automatic permit approval law, enacted in 1998. This law mandates automatic approval for permit applications if agencies fail to act within the specified timeframe. However, implementation has been inconsistent, with agencies often lacking the rules and guidelines necessary to enforce deadlines. Additionally, there is uncertainty about the law’s scope and constitutionality.

Currently it is ambiguous which permits and approvals the law applies to. Therefore, Hawaii’s legislature should take steps to clarify its application and strengthen its enforcement. This might include setting standardized timelines across agencies or providing clarity on the types of permits to which the law applies.

The automatic approvals law could be especially useful if applied to building permits. One model might be a state law in Arizona that approves submissions automatically when local governments miss predetermined deadlines. Arizona law requires approval criteria to be clear and unambiguous. In a court proceeding involving the denial of a permit or license, courts will not defer to previous determinations by the county or local government, protecting applicants from arbitrary denials.

Recommendations for Hawaii

By making third-party permitting reviews a permanent feature of its permitting process and integrating a clearer system of automatic approval, Hawaii can address longstanding problems with its permitting procedures. A successful model would likely include:

Certification standards: Require third-party reviewers to meet state-approved training and qualifications.

Oversight: Ensure that state and county agencies retain the authority to verify and approve third-party recommendations, as demonstrated in Pennsylvania.

Legislative clarity: Provide clear guidelines for how automatic approval laws apply, including timelines and criteria for denials, to reduce ambiguity and improve confidence in the permitting process.

By learning from other states and building upon its existing laws, Hawaii can create a faster and more accountable permitting system that meets the needs of both residents and developers.

Conclusion

Hawaii is at a pivotal moment in its permitting reform efforts as it works to rebuild after the devastating Maui wildfires. Ongoing delays in permit processing demonstrate the continuing need for meaningful reform. Any changes must also respect Hawaii’s unique cultural heritage. The state’s recent emergency initiatives highlight both the urgency of streamlining approvals and also the sensitivities that come with regulatory changes.

Fortunately, better options are available. Several states, including Tennessee, Louisiana, Pennsylvania, and Virginia have successfully implemented expedited permitting systems involving third-party reviewers. These could form a model for making Hawaii’s current system of third-party permitting assistance, which appears to be having some successes, a permanent feature of its regulatory process. Hawaii’s automatic permit approval law also presents an opportunity for reform, though its effect has been limited by imperfect execution and uncertainty over its scope. A potential model is Arizona’s Permit Freedom Act of 2023, which established deadlines for local governments to act on permit applications.

By adopting these strategies—clarifying existing laws and fully integrating third-party review and automatic approvals—Hawaii can move toward a permitting system that is both efficient and responsive to the needs of its communities. These reforms can accelerate wildfire recovery and help alleviate the housing crisis. For changes to be successful, they must be implemented with careful consideration of local concerns, ensuring that economic development and resident priorities remain aligned. If done thoughtfully, Hawaii has the potential to serve as a national model for permitting reform.