A Rise in Unfunded Mandates on State and Local Governments Could Spur Calls for Regulatory Reform in the 118th Congress

Photo Credit: Getty

The Biden administration’s surge in federal regulations affecting small business will likely to induce some calls for regulatory reform during the 118th Congress. Now those small businesses with voices often too small to get heard may have reinforcement.

There also appears to be a substantial rise in regulations, including unfunded federal mandates, with effects on state and local governments. That, combined with small business concerns, could to send the message to policy makers to get something done about overregulation of the economy and society.

It was the union of small business and lower-level governments that led to the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act (UMRA) of 1995 and to the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act that immediately followed in 1996.

Along with the Congressional Review Act in 1995 and the Regulatory Right-to-Know Act of 1999, these were the last major general, overarching reforms of the administrative state. Typically, concerns about overregulation emphasize the plight of business and employers, but it was state and local officials’ mobilization during the 1990s over federal mandates torpedoing their own priorities that resulted in UMRA and subsequent changes. UMRA requires the Congressional Budget Office to produce cost estimates of mandates affecting state, local, and tribal governments above the then-threshold of $50 million, and sought to limit them.

Today, high levels of pandemic and post-pandemic spending and regulation affecting small business, states, and localities may lead to a new alignment that again induces a reluctant Congress to pull back. Recent infrastructure and investment legislation have affected the relationship between the federal and state and local governments to a large degree (not to mention with citizens themselves), likely raising the saliency of federal encroachment on local roles, concerns, and prerogatives.

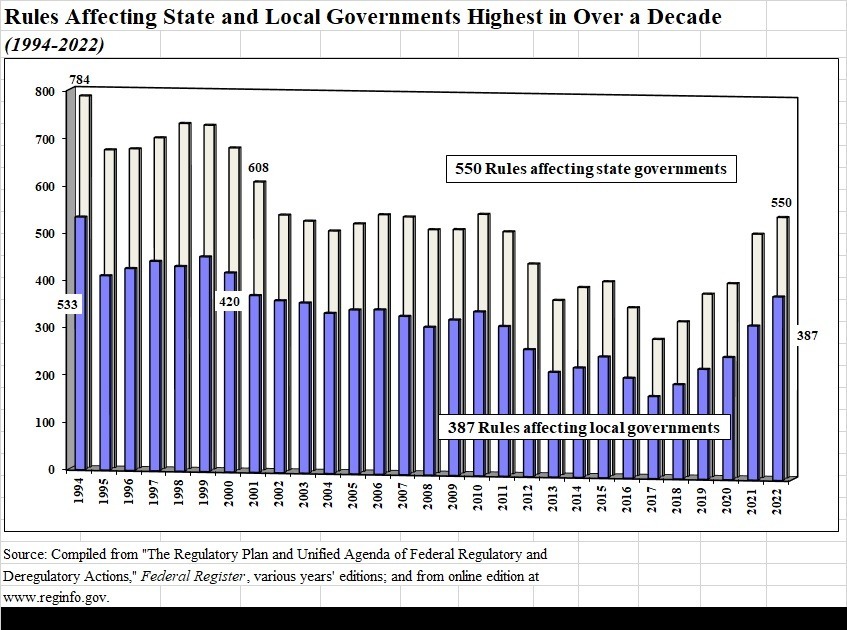

As the figure nearby shows, federal agencies report that 387 of the 3,690 rules in the Biden administration’s Fall 2022 Unified Agenda of Federal Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions pipeline (see a broader analysis of the newly released Agenda and its embodiment of Biden’s “Whole-of-Government” interventionist campaign here) will affect local governments. This new tally represents an increase of 50 percent over Trump’s last year count of 258 (and is 19 percent greater than Biden’s count in 2021). These totals include all rule stages—active, completed, and long-term. In Trump’s fall 2020 Agenda, 46 of 258 local actions had been deemed “Deregulatory” for his “one-in, two-out” executive order purposes, which brings Biden’s “real” increase to 82 percent over Trump’s “net” of 212 rules affecting localities. As the figure shows, rules affecting local governments have not been this high since 2000, when there were 420.

Turning to the total number of regulatory actions affecting state governments (with can overlap with rules affecting localities), we find 550, a 34 percent increase over Trump’s tally of 409 total actions affecting those bodies in 2020 (of which 72 had been deemed “Deregulatory” across the active, completed, and long-term stages). Rules affecting state governments have not been this high since 2001,when there were 608.

The number of rules affecting state and local governments has not reached the 1994, pre-UMRA levels depicted in the chart (784 and 533, respectively), but that appears to be where things are headed. State and local concerns could again motivate long-absent regulatory reform enthusiasm, particularly where legislation and rules generate new mandates that prove unfunded,.

Note that concerns over federal mandates on local and state governments had never actually evaporated, even pre-pandemic and even pre-Trump. At the 2016 Legislative Summit of the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), for example, a “Standing Committee on Budgets and Revenue” issued a resolution asserting: “The growth of federal mandates and other costs that the federal government imposes on states and localities is one of the most serious fiscal issues confronting state and local government officials.” Even in that pre-pandemic era, the NCSL called for “reassessing” and “broadening” the 1995 Unfunded Mandates Reform Act.

That same year, several state attorneys general wrote to House and Senate leadership expressing concerns over federal agencies’ “failing to fully consider the effect of their regulations on States and state law,” and issued an appeal for strengthening the Administrative Procedure Act.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reports that between 2006 and 2019, 190 laws were enacted that imposed intergovernmental mandates on states and localities, with 420 mandates contained within these laws. As it ends before 2020, this CBO depiction does not cover pandemic and post-pandemic legislation that has escalated since then or the regulatory mandates that can derive from such laws as agencies set about acting unilaterally.

According to this official CBO data, while most did or do inflict costs, few of the mandates through 2019 were deemed to have imposed costs on states and localities exceeding the statutory threshold calling for official estimates (aggregate direct costs during any of the mandate’s first five years of $50 million in 1996; $77 million now).

For their part, agencies tend to claim that few of their rules affecting states and localities impose unfunded mandates on them. That can be blamed on their own reluctance to acknowledge costs, but also may be because the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act is not applicable to many rules and programs, which may prove an element of future mobilization for reform. Of the 2,561 “Active” rules in the Fall 2022 Agenda for example, only three are admitted to impose unfunded mandates on state, local, or tribal governments—two related to tobacco standards for flavoring in cigars and cigarettes and one on health-related electronic signatures certification.

Among 443 “Completed” actions, only the Environmental Protection Agency’s amendments on “National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants for Major Sources: Industrial, Commercial, and Institutional Boilers and Process Heaters” is acknowledged as an unfunded mandate. And despite all the aggressive regulatory plans that progressives have in store, there are only two “Long-term” actions acknowledged to impose unfunded mandates: drug labeling barcode requirements and the Department of Labor (refusing to accept the Supreme Court stay of its actions) ongoing pursuit of “COVID-19 Vaccination and Testing Emergency Temporary Standard” as a proposed rule.

The Unified Agenda does recognize and report upon a few additional unfunded mandates when one selects for private sector mandates as opposed to those affecting state and local governments, but not many: only 13 Active, five Completed, and four Long-term rules, all probably undercounts, are presented. Given the return of significant rule-making to pre-Trump levels, there might be more to the story.

Rule counts that affect not only the private sector but state and local governments are on the upswing. It has been over a decade since rules affecting lower-level governments have been as high as they are now. Meanwhile, the disclosure of the mandates they contain within their pages are a mess, much like other regulatory cost and impact disclosures.

The 1996 post-UMRA drop-off in rules in the chart above could happen again. Rectifying the current surge in new regulation should be a core element of Congress’ regulatory liberalization agenda.